Parcellation Evaluation

Brain parcellation selection: An overlooked decision point with meaningful effects on individual differences in resting-state functional connectivity

The human brain is segregated into a series of large-scale functional networks comprised of widely distributed regions. Exploration of these functional networks has been conducted using an array of techniques including clustering methods such as gaussian mixture models (Lashkari et al., 2010; Yeo et al., 2011), meta-analytic connectivity methods (Eickhoff et al., 2011; Power et al., 2011), edge detection methods (Gordon et al., 2016; Laumann et al., 2015), multi-modal methods (Glasser et al., 2016), among many others (Schaefer et al., 2018; Baldassano et al., 2015; Blumensath et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2009). This work has given rise to numerous brain parcellation schemes that detail the specific brain regions that comprise each of the functional networks. Though the primary goal of these parcellations is to reveal brain organization, cognitive, developmental and clinical research has frequently used the parcellations as a means of identifying these networks in subjects to examine individual differences in the functional organization of the brain based on cognition (Lopez et al., 2019; Murphy, 2020), age (Jalbrzikowski et al., 2019; Lopez et al., 2019; Satterthwaite et al., 2013; Sylvester et al., 2018) or the presence of psychopathology (Fan et al., 2019; Lydon-Staley et al., 2019; Reggente et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2019). Brain parcellations are used to extract data from a set of parcels, or brain regions, that comprise the pre-identified functional networks. These data are then used to examine network-specific properties such as within-network connectivity (Fan et al., 2019; Karcher et al., 2019; Lydon-Staley et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019), or graph theory metrics such as global efficiency and modularity (Bullmore & Sporns, 2009; Grayson & Fair, 2017; Stumme et al., 2020) to draw conclusions about global properties of brain function and individual differences in network properties as a function of development or across clinical groups. The widespread adoption of these parcellations in cognitive neuroscience broadly (Geerligs et al., 2015; Finc et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2020; Weis et al., 2020), and specifically within developmental (Baum et al., 2020; Karcher et al., 2019; Lopez et al., 2019; Tooley et al., 2020) and clinical research (Fair et al., 2013; Xia et al., 2018; Yerys et al., 2019) has allowed for extensive exploration of individual differences in functional brain organization.

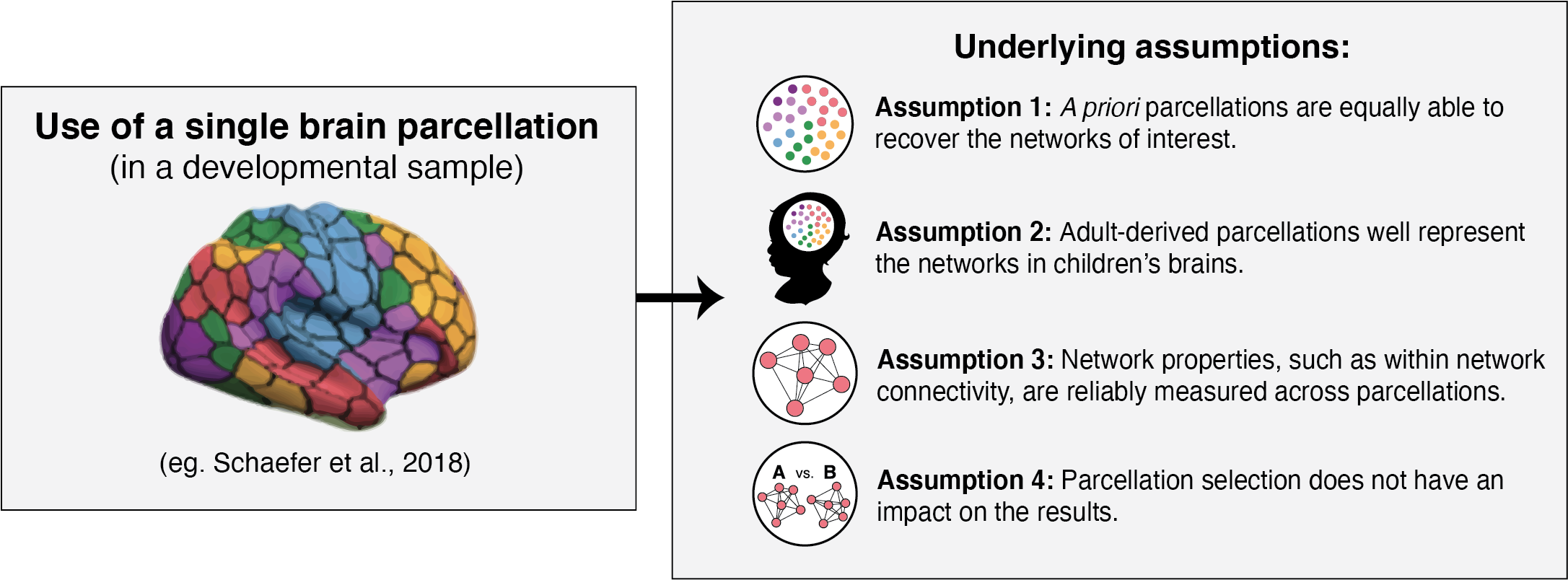

The application of brain parcellations is now commonplace. However, this practice hinges on four major assumptions that, to our knowledge, have not been evaluated empirically. The first assumption is that the networks of interest are well recovered in the data extracted from a parcellation, such that the extracted data can be used to construct network-specific measures. Furthermore, as most studies rely on a single parcellation, it is assumed that the various parcellations are equally able to capture or recapitulate the networks of interest. Given that adult-derived parcellations are frequently applied to data from developmental samples (Alarcón et al., 2018; Fair et al., 2013; Jalbrzikowski et al., 2019; Lopez et al., 2019; Satterthwaite et al., 2013; Sylvester et al., 2018; Yerys et al., 2019), a second assumption is that these parcellations reflect the topography of functional networks in children, and thus that the networks of interest will be accurately captured by these parcellations in developmental samples. Third, many of the available parcellations share highly similar labeling schemes, where networks that share similar spatial extents across the various parcellations also bear the same network labels (e.g., “default network”, “dorsal attention network”, etc.). This shared labeling has led to the assumption that the networks that are represented across the parcellations can be considered analogous. In other words, the default network identified in parcellation scheme A is the same network as the default network identified in parcellation scheme B. Thus, the parcellations are assumed to produce reliable measurement of network properties such as average within network connectivity. Finally, though some studies replicate results using a series of parcellations (Finc et al., 2020; Geerligs et al., 2015; Luppi et al., 2021; Tooley et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2018), a majority of studies only employ a single parcellation. This practice presumes that the various parcellations can be considered interchangeable, such that parcellation selection does not have an impact on the results obtained.

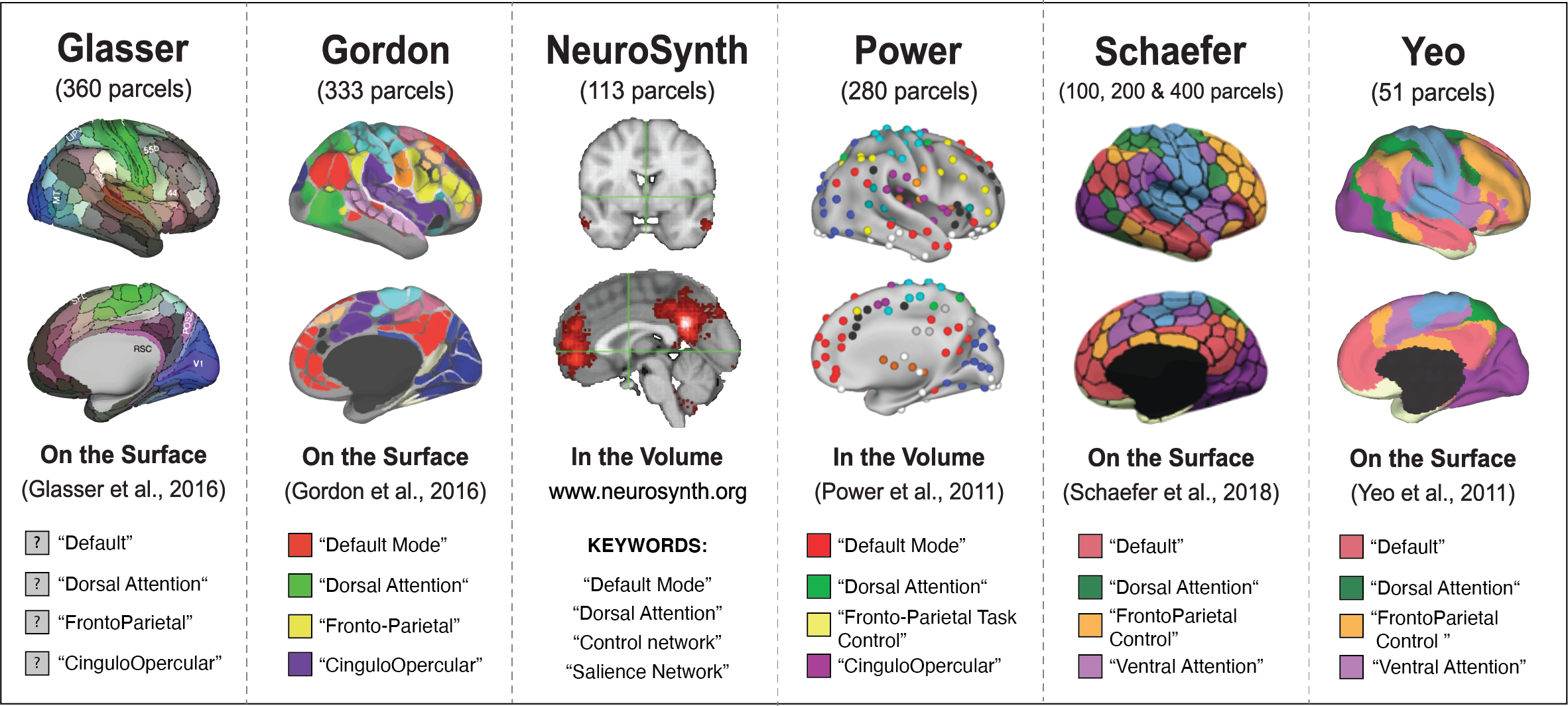

In the present study, we examine these four assumptions. To do so, we selected a set of parcellation schemes commonly used (Glasser et al., 2016; Gordon et al., 2016; Power et al., 2011; Schaefer et al., 2018; Yeo et al., 2011). We were also interested in assessing the extent to which the meta-analytic platform NeuroSynth is able to produce sensible networks maps. NeuroSythn.org allows researchers to identify task-evoked activity mappings (Yarkoni et al., 2011; Lieberman & Eisenberger, 2015) using keywords. As researchers often refer to the primary functional networks when discussing task-evoked activity, primary functional networks have also begun to be identified using NeuroSynth’s meta-analytic approach (Franzmeier et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). We were interested in examining how well the NeuroSynth platform is able to identify functional networks, so included maps of four primary networks of interest (the default network, the control network, the dorsal attention network, and the salience network) derived using NeuroSynth.org.

The parcellation schemes examined:

Using the eight selected parcellation schemes, we examined the following questions: 1) Are the parcellations equally able to recover the networks of interest (i.e. does the parcellation-extracted data recapitulate the expected correlational network structure defined by the parcellations)? 2) Do these adult-derived parcellations well represent the networks in children’s brains? 3) Are network properties, such as within network connectivity, reliably measured across parcellations? 4) Does the parcellation selected impact the results with regard to individual differences in network properties? To evaluate the fourth assumption, we examine three common questions about individual differences in functional brain organization, including whether functional connectivity within networks of interest vary as a function of age, environmental experience and cognitive ability. Here, we focus on poverty as a measure of environmental experience. We examine these four assumptions in two large samples of children and adolescents, focusing on four primary networks of interest that are widely studied and derived using parcellation schemes: the default, control, dorsal attention, and salience networks.

Discussion of Results

(for full results and discussion see Bryce et al., 2021)

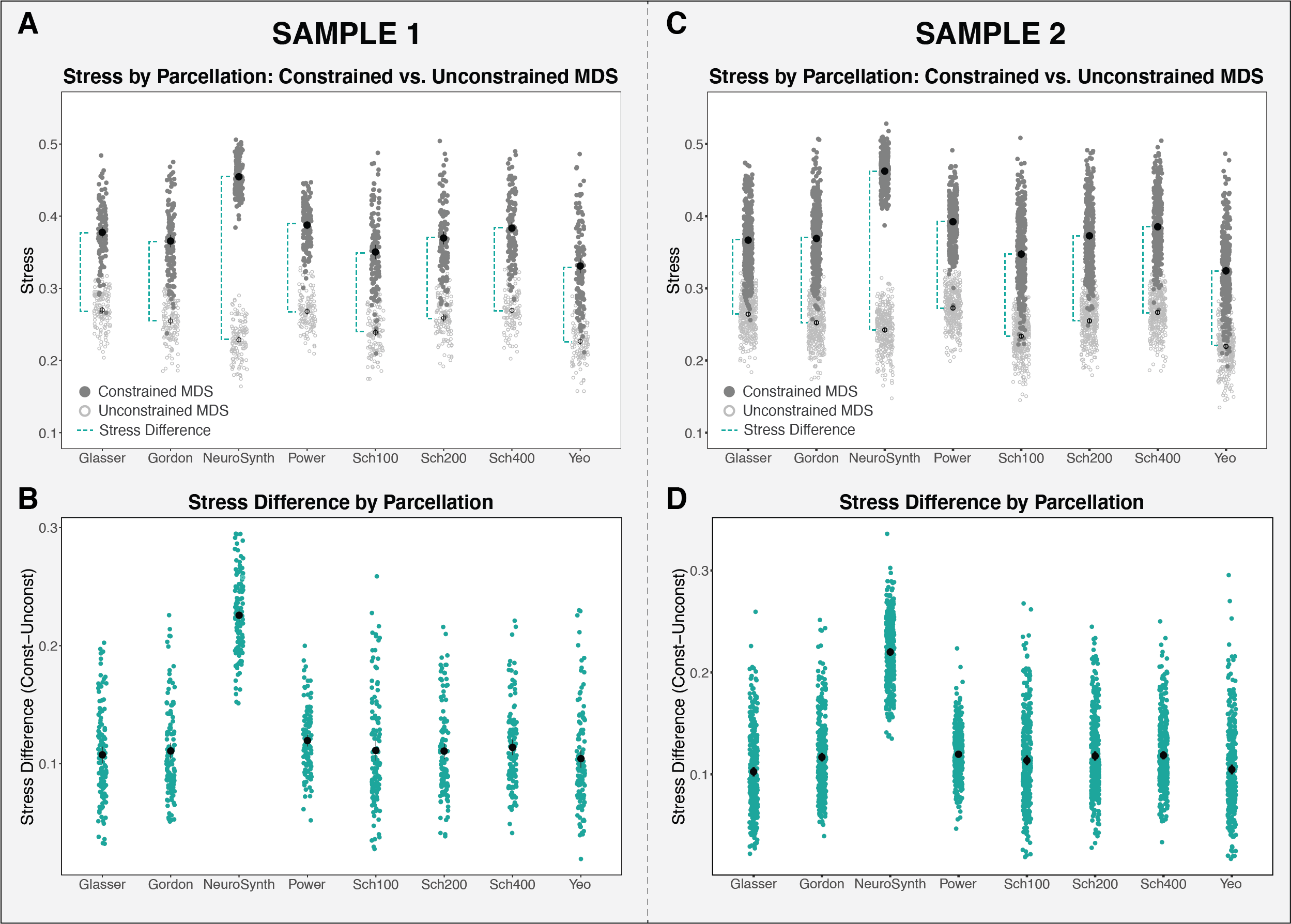

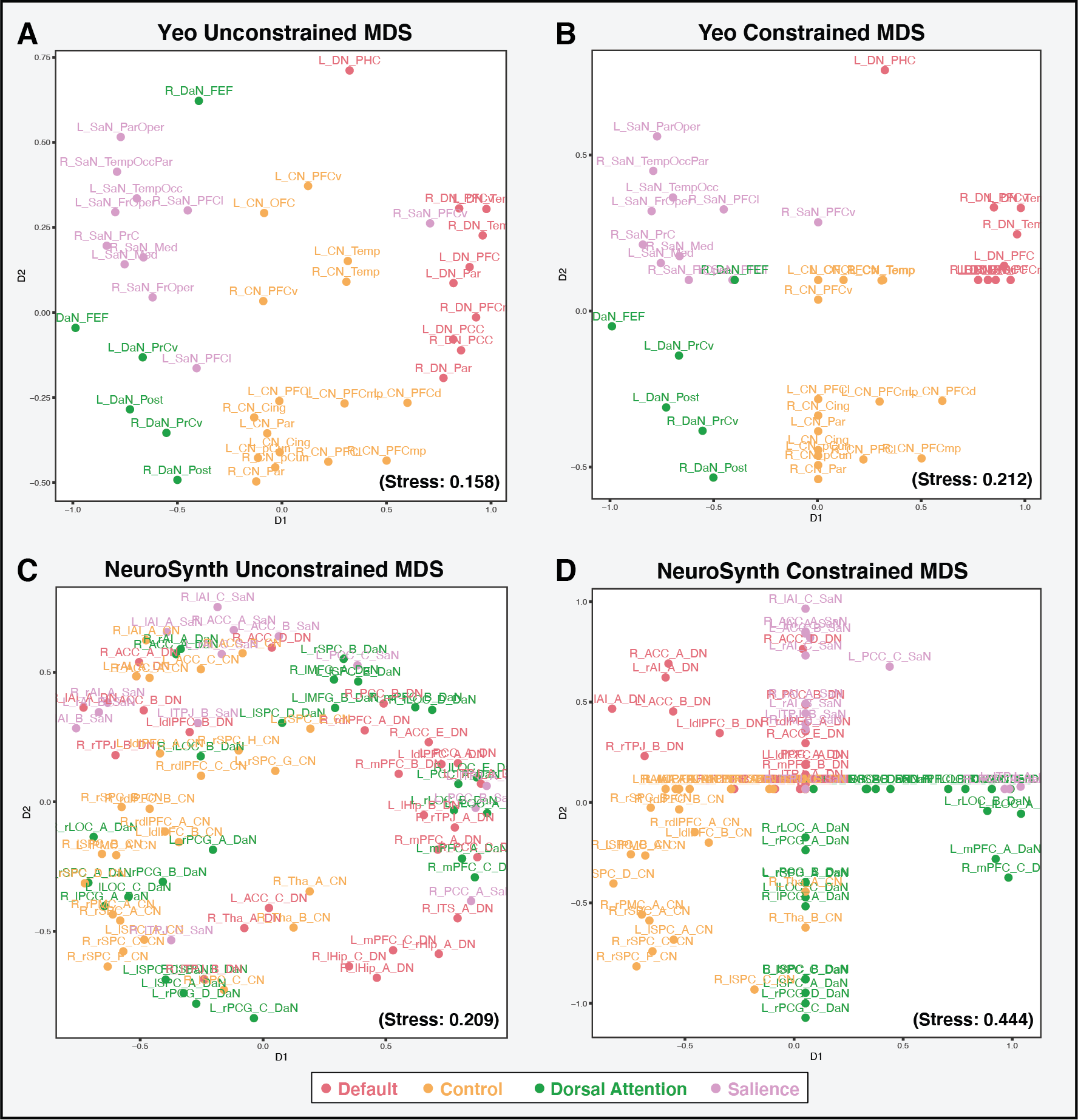

Question 1. Are the parcellations equally able to recover the networks of interest (i.e. does the parcellation-extracted data recapitulate the expected correlational network structure defined by the parcellations)?

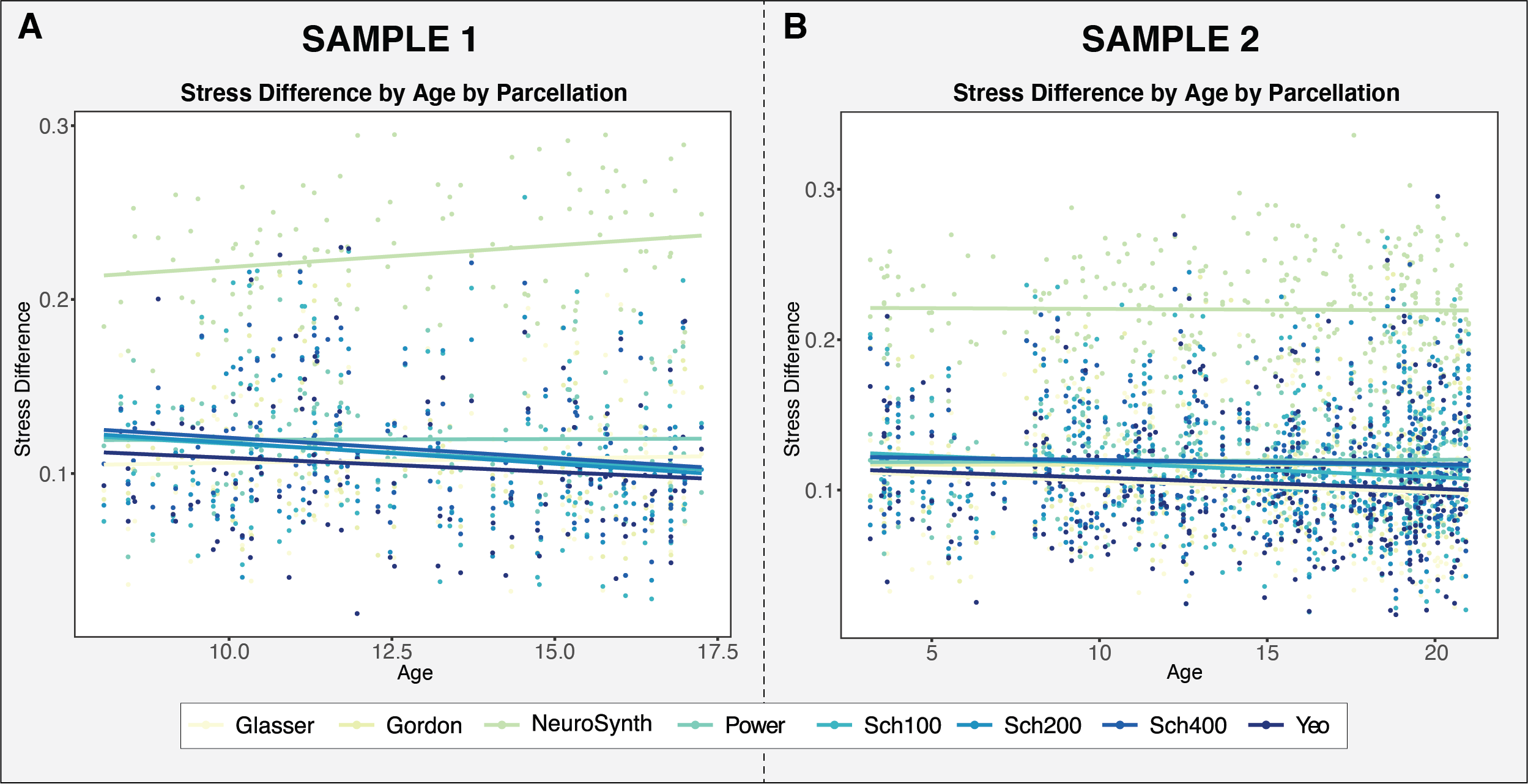

We used a multi-dimensional scaling technique to assess the extent to which the networks of interest are recovered in data extracted from the eight parcellations evaluated. A lower stress difference indicates that the networks of interest are well-recovered in the extracted data.

With the exception of the NeuroSynth-derived maps, the other seven parcellations performed similarly at recapitulating the networks of interest in the resting-state functional connectivity data. This suggests that various parcellations are able to capture network-level functional brain organization, when applied as a priori schemes.

Question 2. Do these adult-derived parcellations well represent the networks in children’s brains?

To assess whether the functional networks identified in parcellation schemes developed in adults are well-represented in data from children, we examined whether the stress difference ––which estimates how well the extracted data recapitulate the networks –– varies as a function of age. If stress difference decreases as a function of age, this would suggest that the networks of interest are less identifiable within data from children than adults.

The application of adult-derived brain parcellations in developmental samples presumes that these parcellation schemes are representative of the primary functional networks in children. By examining the extent to which network recapitulation varied as a function of age and parcellation, we were able to assess the validity of employing these parcellations in developmental samples. With the exception of NeuroSynth, the parcellations show no significant change in stress difference with age in either sample, including one with a wide age range (3-21 years). These findings suggest that the networks of interest in parcellations derived from adult data are represented equally well in resting-state data from children as adults.

Question 3. Are network properties, such as within network connectivity, reliably measured across parcellations?

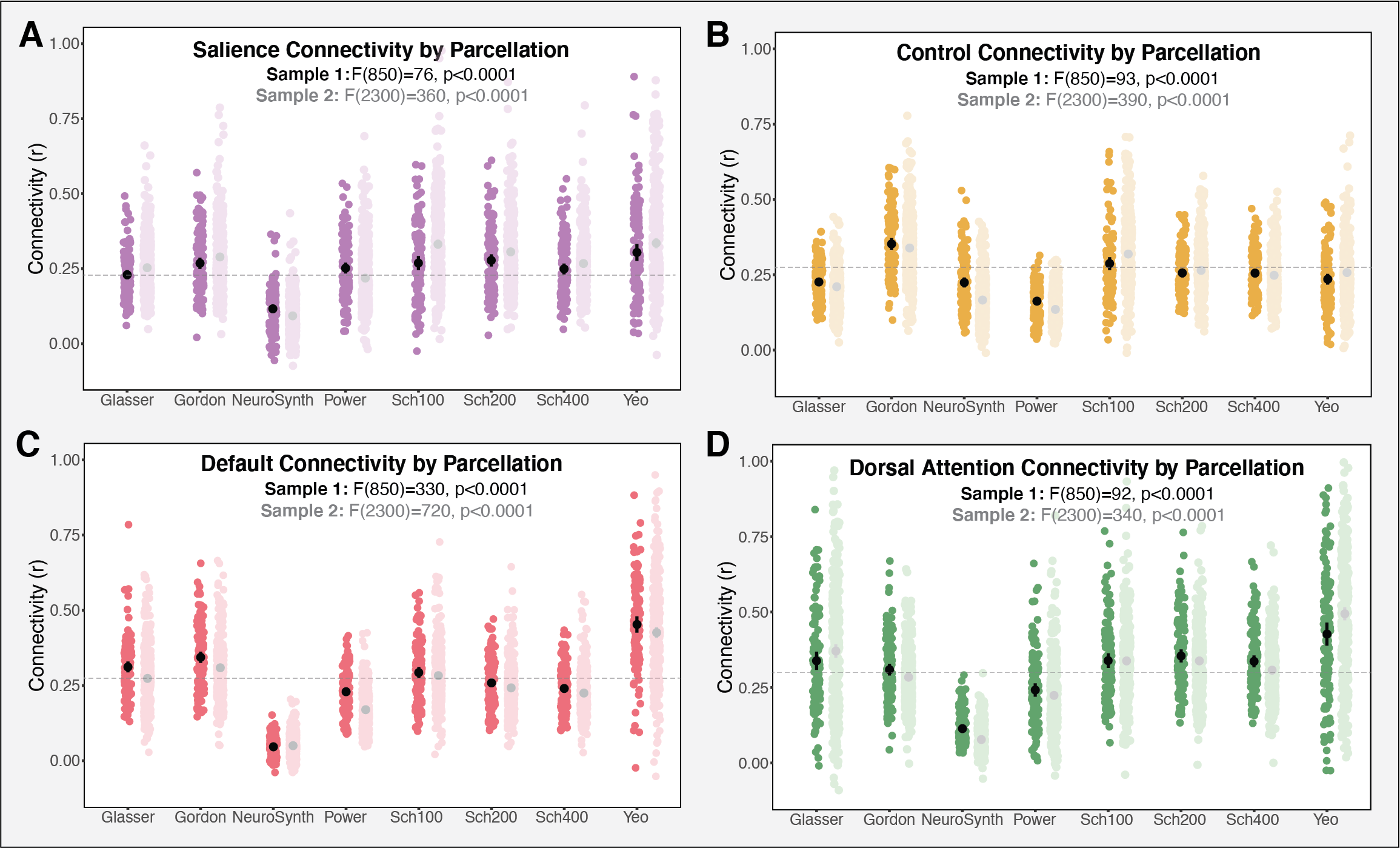

Measures of average functional connectivity by parcellation for each of the four networks of interest. Connectivity varied significantly across the parcellations in all the networks assessed, including (A) salience (B) control (C) default and (D) dorsal attention in both Sample 1 (dark color) and Sample 2 (light color). Grey dashed line represents the grand mean connectivity (Sample 1) for each of the networks.

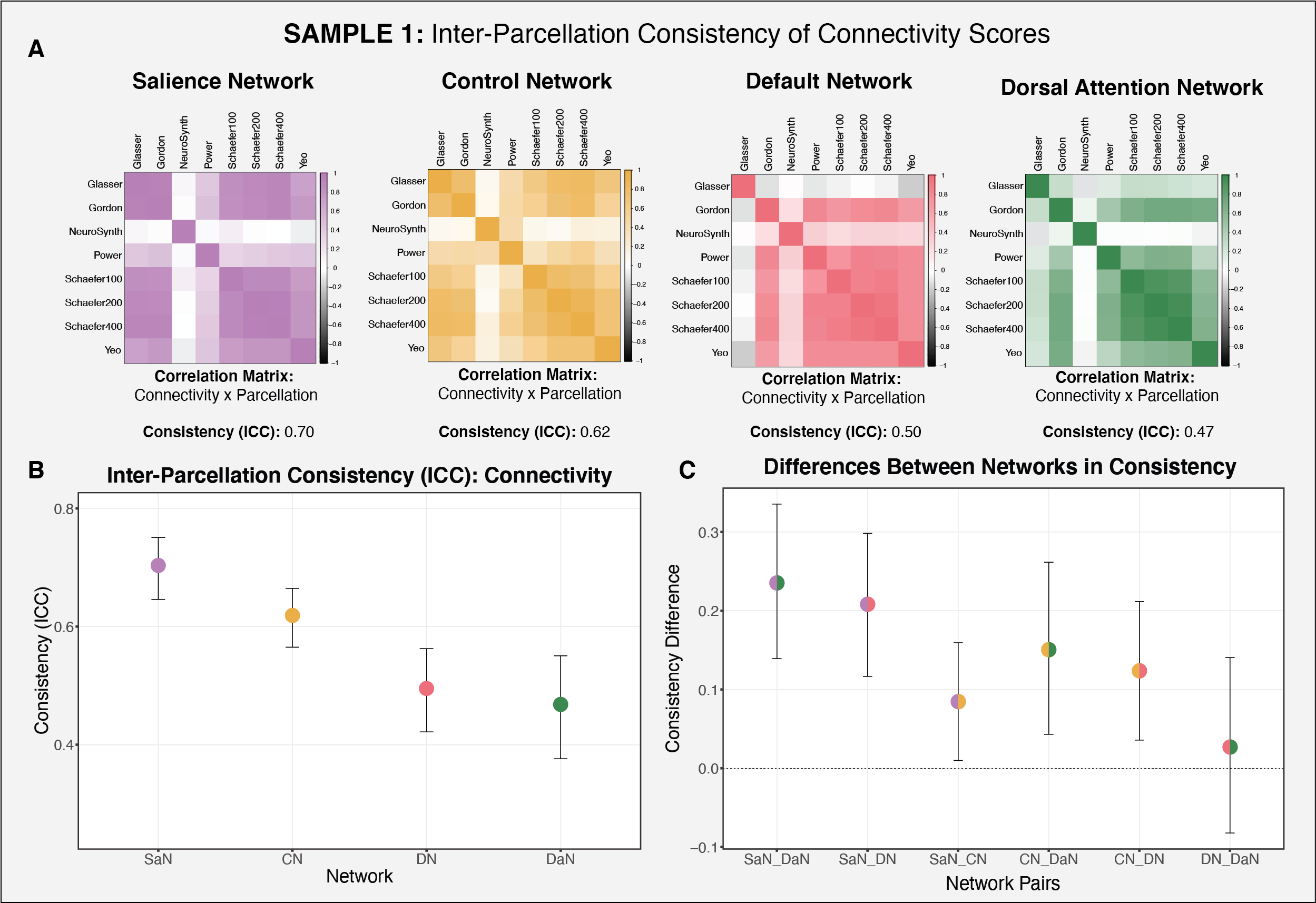

We examined whether the various parcellations produce reliable measures of within-network connectivity, which would imply that subjects maintain consistent rank order in functional connectivity within a particular network across the parcellations examined. To examine the reliability of the parcellation-derived connectivity scores, we calculated ICC measures for each of the networks of interest.

Measures of within-network functional connectivity varied meaningfully across parcellations, particularly for the default and dorsal attention networks.The salience network was the least consistently labeled network across the various parcellations, but produced the most reliable connectivity estimates, followed by the control network. The default and dorsal attention networks exhibited the lowest consistency.

Question 4. Does the parcellation selected impact the results with regard to individual differences in network properties?

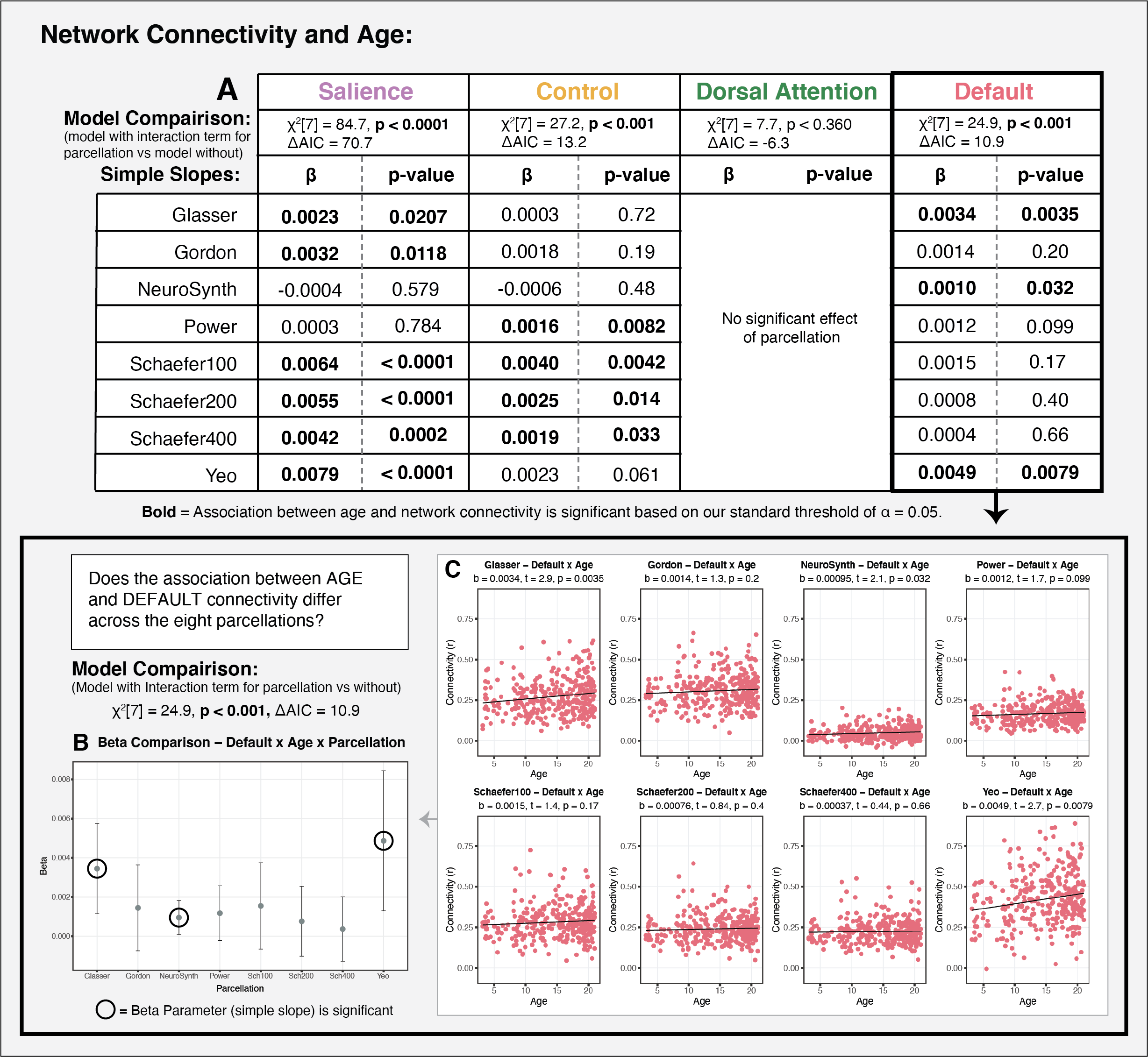

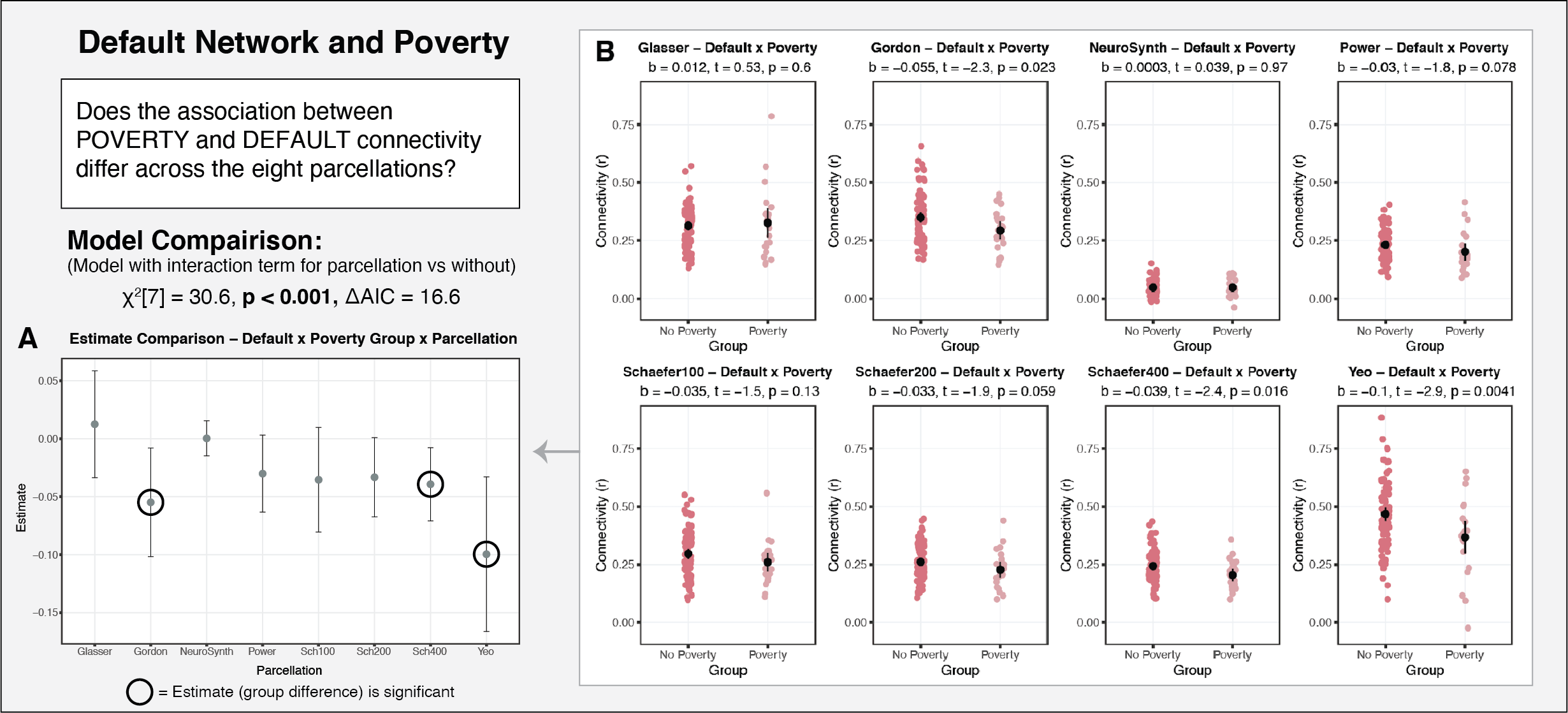

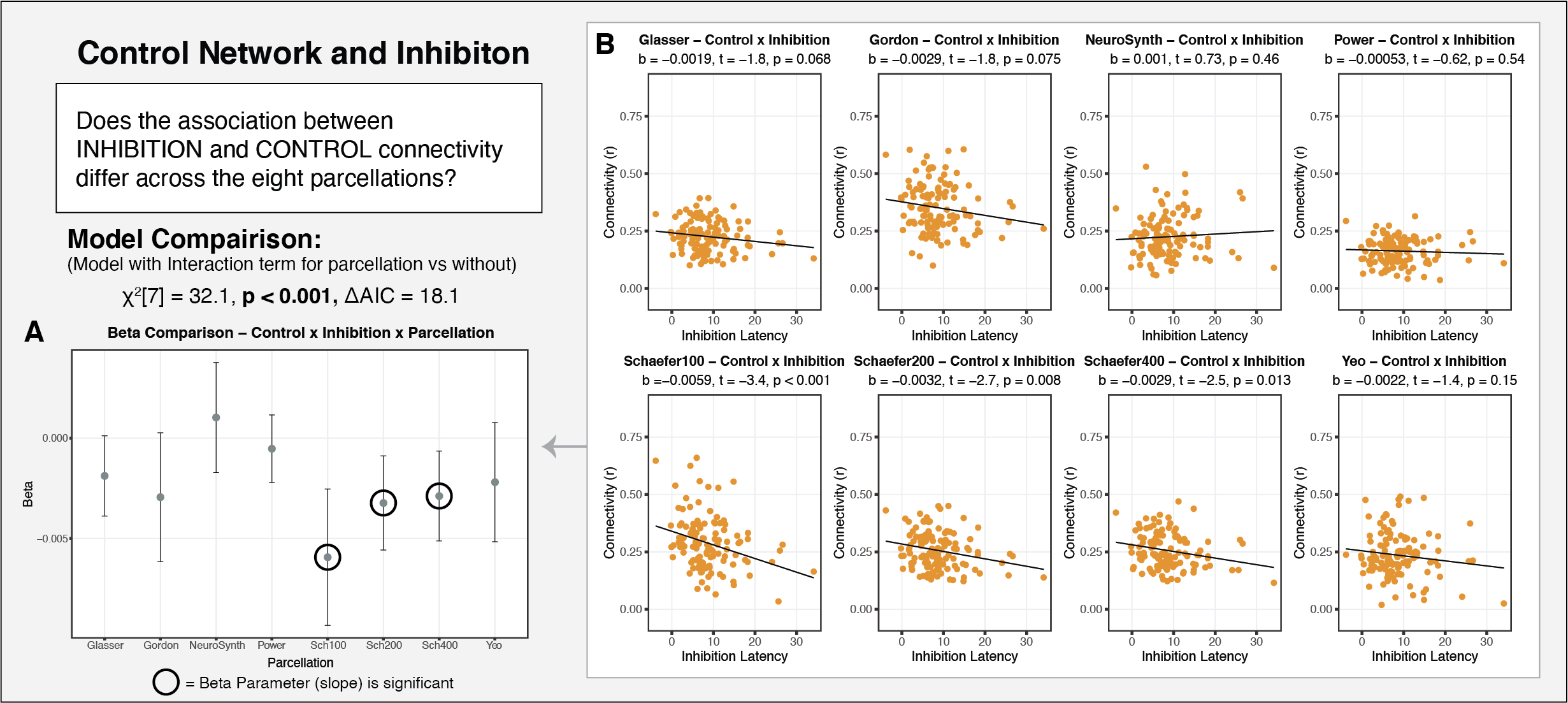

Finally, we also assessed the extent to which parcellation selection impacts the interpretation of putative results regarding individual differences in functional connectivity as a function of age, poverty, and cognitive function.

In developmental and clinical research, it is common practice to conduct analyses only using a single parcellation scheme. This assumes that parcellation selection does not have an impact on the interpretation of the results. Our findings challenge this assumption. A range of analyses focused on differences in functional connectivity by age, poverty, and cognitive function, revealed that parcellation selection had a significant and meaningful impact on the interpretation of results. For each of the associations examined, roughly three of the eight parcellations produced significant results, while the other five produced null results. Furthermore, we observed meaningful variability not only in the statistical significance of the estimates, but also in the point estimates. These findings suggest that parcellation selection can have a significant influence on the results obtained in studies examining individual differences in resting-state functional connectivity, particularly if only a single parcellation is used.

Conclusion

We examined a series of assumptions made when a priori brain parcellation schemes are used to identify the canonical functional networks and examine individual differences in functional connectivity. We found that the networks of interest were equally well recovered in data extracted using a series of eight parcellations, with the exception of NeuroSynth. Furthermore, the networks of interest were equally well represented in pediatric data as in adults. However, within-network functional connectivity showed notable variability and poor consistency across the parcellations examined for each of the four networks. Furthermore, parcellation selection meaningfully impacted the magnitude and significance of associations between functional connectivity and age, poverty, and cognitive function. Our findings suggest that work that depends on a priori parcellations for network identification may benefit from the use of multiple schemes to confirm the robustness and generalizability of results. Furthermore, researchers looking to gain insight into functional networks my benefit from employing more nuanced network identification approaches such as using densely-sampled individual data to produce individual-derived network parcellations. Indeed, recent work examining idiosyncratic network topography, has illustrated meaningful individual differences in topography associated with cognition and behavior (Bijsterbosch et al., 2018; Kong et al., 2019). A transition towards precision neuroscience in cognitive work in general, and in developmental and clinical work specifically, is likely to improve the characterization of functional brain organization, and links with cognition and behavior, in a way that is unavailable when methods are confined to group averaged approaches.